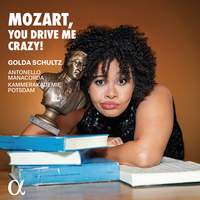

Interview,

Golda Schultz on Mozart's Women

In the run-up to her appearances as Fiordiligi in Covent Garden's Così fan tutte, Golda spoke to me about the wonderfully three-dimensional nature of Mozart's female characters, the frustration she feels about the way these women are so often misunderstood or mocked by directors and audiences alike, why the three Da Ponte operas feel 'more relevant than ever' today, and the role which 'changed her as a person' - even though she never wants to sing it again...

What is it about Mozart that 'drives you crazy'?!

I honestly don’t think there are many composers who portrayed humanity in all its complexity as well as Mozart did, or demonstrated so clearly that it's possible to find beauty even in the middle of all the chaos and darkness that often surrounds us. I love Puccini and Verdi, and I’ve been a Beethoven girl from Day One… but ask me for a story that’s about the joy, craziness and hard work of being a human being in this world and I will send you straight to Mozart. And women are the beating heart of these stories. In all three Mozart/Da Ponte operas there’s not a single female character who isn’t a fully-drawn woman with wants and needs – right down to Barbarina!

What was your first Mozart role?

I started with the Countess, which is probably the role I’ve sung the most in my career. I began working on it as a student in Cape Town, and the first time I sang it was in an abridged performance for schools. (I say ‘abridged’ but really it was just the first two acts, so the whole thing ended with the chaos and madness of the Act Two finale. No closure for you, kids!)

That was back in 2006, then in 2011 when I was a member of the Opera Studio at the Bavarian State Opera I was offered an amazing opportunity: the singer who was scheduled as the Countess had to withdraw, and the studio heads Tobias Truniger and Henning Ruhe told Nikolaus Bachler (the Intendant at the time) that they thought I might be ready…

In the meantime Anja Harteros had stepped in, but she very graciously said she would love to share the role with a young singer. I’ve had a lot of wonderful women be extremely kind to me in this business, and Anja is one of them: when I got into rehearsals with Simon Keenlyside as the Count and Luca Pisaroni as Figaro I had to pinch myself!

How did you start getting under the character's skin?

I think I’m very fortunate because of where I started: coming from South Africa and not having much access to seeing people do these roles, I had to go with what was in front of me. I’m always interested in watching other artists, but I’m much more intrigued by what’s on the page because that’s where I find my freedom.

We usually meet Mozart’s characters in the middle of their story, when they’re in crisis, but what fascinates me is trying to find the beginning of that story. This is Opera 101, but let’s not forget that Le nozze di Figaro happens some time after Il Barbiere di Siviglia: Rosina comes to this marriage after years of being locked in a room and denied freedom, and in Nozze we see her trying to work out how to navigate her new situation. It makes me think of that story of the bird in the cage that flaps its wings saying ‘I can’t get out!’...but then the door is opened and he says ‘You don’t understand: I can't get out’.

How these women cross the bridge from trauma to resilience is what makes the drama so compelling. Sometimes people respond to crises with violence, sometimes with a viper’s wit (like Marcellina, struggling with becoming invisible because of her age), sometimes with goofy humour. I’m definitely in the last category: my friends will all tell you I’m the one who’ll laugh inappropriately in stressful situations!

Speaking of laughter, I think it’s important to remember that the Countess is still that girl we met in Barbiere who was so full of fire and fun. I sang my first Countess when I was only 26, and I didn’t have all of the heavy relationship drama in my bag back then - but I did know what it was to be a young person longing to get out and make things happen. As I get older I find more pathos in her, but I don’t forget the humour; I don’t think I’m not funny just because I’m 40 now!

Have any specific productions altered your perspective on her?

People ask me if I ever get bored of singing the Countess, but there’s always more to discover: perhaps I’ll hear a detail in the score that I missed before, perhaps someone sings a line in a certain way and that prompts me to respond differently. Take that trio in Act Two, ‘Susanna or via sortite’: that can be an almost farcical game of cat-and-mouse or an absolutely horrendous moment of domestic violence.

When I was singing it in Vienna last October I discovered a violence even in the Countess: I thought ‘Woah girl, you’ve got claws!'. The Count is a volatile man, but this is not an unequal match: when she gets fired up she’s his equal, and that makes her an extremely dangerous woman to be around. She suddenly became someone that I didn’t know, and that’s quite fun. The way I see it is that I keep getting to know myself better every day of my life: why wouldn't I give the character the same respect that I give myself?

What sort of insights have you gained from singing different roles in the same opera?

I love that these operas don’t have a leading lady as such: there are usually two women who swap it out between them rather than competing for the limelight. The Countess and Susanna give each other space to be centre-stage when they need it, and it’s the same with Dorabella and Fiordiligi – when Dorabella starts ‘Smanie implacabili’ the other two women step aside as if they’re saying ‘Oh yeah, there she go..!’.

After singing the Countess many times, La Scala invited me to do Susanna: I decided I would only do it once, because I don’t have it in me to have people be so grabby with me on stage. I’d always had a bit of Susanna-envy because I wanted to play the happy love-story, but once I started looking at it I realised it was not a love-story I liked: there’s no trust in that relationship, and Susanna does not seem safe in it. She’s not safe in her relationship, and she’s not safe at work; sure, she has a wonderful relationship with the Countess, but the nature of her employment means that the Countess is always making demands on her too…

Once I started digging deep into Susanna’s character, I instantly wanted to make sure that I, Golda, became a safe space for people who didn’t feel safe in their working environment. Now when I play the Countess I try to find a way to make it so that the person who sings Susanna can sometimes let go and not be consistently performing around her employer. Cracking open that character changed me as a person. But would I want to play her again? No way!

You're about to sing Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte at Covent Garden: how sympathetic a character do you find her?

For me Fiordiligi really is the heart of Così. She doesn’t just want to act correctly: she genuinely wants to do what’s morally right, because she has a wonderful ideal of what it is to be a person. That’s where the humour and the pathos come in, because we look at her and think: ‘Oh honey, you don’t even know what you don’t know yet!’. That’s Così in a nutshell: it’s the ‘School of Love’ (or ‘School of Hard Knocks’), so you know these people are going to get hurt but also going to be so much stronger for it.

Lots of people say ‘I hate Così, it’s such a trash opera!’, and I think that’s where we as an audience fail the work: because we don’t want to see ourselves reflected in these very fallible characters. Nobody wants to identify with people who make such atrocious mistakes - who use other people as badly as those men use those young women to prove a point, or to be so flip-floppy as the women are perceived to be.

It’s not easy to watch, but Mozart and Da Ponte are making a deep commentary on what it is to be a woman under pressure. These women say No, regularly and emphatically – and nobody listens. To have your voice ignored, and then to be called inconsistent even though you said what you said over and over…that’s a hard indictment on our society.

People often ask me ‘How do you sing Mozart and all of these archaic operas in 2024?’ And my response is ‘Do you think we’ve developed past this? That’s why these operas are still relevant: because we haven’t learnt the lessons yet!’ But even through all of that there is still beauty – all of these characters are finding themselves, even if it’s a painful process.

Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni is another character who's often mocked by the other characters - and even laughed at by the audience, despite being in a desperate situation. Do you think it's harder to elicit sympathy for her if the opera's set in modern times, when women are often expected to be able to 'move on' from brief sexual relationships with equanimity?

Regardless of the time-period, I don’t think anyone should be expected to be OK with being lied to, manipulated and generally screwed over by someone who gives no thought to the consequences of their actions! Imagine you’re someone who is very focused on your own goals, then you’re confronted with another person who so wants to be a part of your life that they will do anything you ask. Eventually you draw your line in the sand and include them in your life-plan…at which point they disappear. They don’t even tell you they’re leaving – it’s the ultimate ghost!

The crux of the matter is that this woman who is so strong in her sense of self has that sense of self completely ripped away: that’s heart-breaking, and every time I see people laughing at Donna Elvira I get so mad! How can you laugh at this Neanderthal of a man, Leporello, being convinced into treating a woman with such disrespect by an absolute sociopath? I’m so over the whole ‘Don Giovanni, the sexy bad guy of opera!’ thing. He’s so one-dimensional, and Mozart shows us that very clearly.

Even Donna Anna, who suffers two very traumatic events within the first twenty minutes of the opera, has been framed as an unreliable narrator by some directors - and the moment near the end where she asks her fiancé to give her more time to grieve is sometimes greeted with a laugh by the audience...

I have no time for the argument that maybe Donna Anna lied about the rape. If you really listen to that recitative before 'Or sai chi l'onore', that’s a woman who was sexually assaulted, and anybody who doesn’t hear that needs to understand what enthusiastic informed consent looks like. She says ‘I assumed it was you, my lover…but it wasn't you, and I wasn’t given an opportunity to scream until the very last minute’. Then she does a wonderful thing: she actually tries to hold on to her attacker so he can be held to account.

People go on about the shame she feels after her father’s killed: have they never heard of survivor's guilt? Modern psychologists have explained very clearly how it can ruin lives, and Anna is a case-study in that and the process of grieving. And even then, the world is still making demands on her: Ottavio’s sympathetic at first, but by Act Two he’s essentially saying ‘Sorry your dad died, but can you just get over it already?’. In today’s society there’s this pressure for people who've suffered bereavement and trauma to get back to normal and get back to work, and that’s the same with Anna and Elvira: are they not allowed space to grieve and to be angry?

In ‘Non mi dir’ we hear her telling Ottavio that maybe they can be happy together one day…That’s a break-up aria if ever I heard one: they aren't going to be happy together one day, but she’s handling it with a very feminine understanding that this could turn into an extremely toxic situation. How often as women do we frame ‘No’ as ‘Maybe later..?’ in the hope that the persistent guy will eventually move on? These stories aren’t old: they’re still happening right now, and that’s what makes Mozart so compelling.

Figuring out how to convey all of this in the way that I sing the music is such an exciting process: ‘How am I going to make it clear to people that I’m singing about processing grief? What does that sound like?’. On one level this album is my love-letter to Mozart, but it’s also me trying to invite people to listen a little deeper: don’t just get stuck on how pretty it sounds. The beauty doesn’t require my involvement in the equation, because it already exists – I’m there to bring out the complexity so that someone else can hear and process it for themselves.

Golda Schultz (soprano), Antonello Manacorda, Kammerakademie Potsdam with Julie Roset, Amitai Pati, Simone Easthope (sopranos), Ashley Dixon Santelli (mezzo), Milan Siljanov (bass-baritone)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC