Interview,

Kirill Gerstein on Music in Time of War

Kirill spoke to me from Berlin last month about the importance of placing the music of both composers in its historical and cultural context, some of the historians and musicologists whom he enlisted in service of that aim, and why music composed in dark times so often contains 'an incredible amount of exuberance, kaleidoscopic colour and life-affirmation'...

What prompted your interest in Komitas's life and work, and the decision to bring him together with Debussy on this album?

Komitas and Debussy were more than just contemporaries: for a while they actually moved in the same circles. Komitas spent time in Paris with D’Indy and Saint-Saëns, where he attended the International Congress of Music and the driving force behind cultural events for Armenians in the city; Debussy heard his music and expressed enormous admiration for it.

I was always touched by Komitas’s music and its story, and in a way I think it’s very appropriate for me as a Jew not to be focused on our holocaust but on another genocide. These tragedies all have their own specific stories, but on another level they’re universal; these atrocities have direct parallels with what’s happening with innocent civilians right now in Ukraine, Sudan, Gaza…

On the one hand I wanted to shine a light on a marginalised tragedy from 100 years ago; on the other hand, I think we’re still living out the repercussions of that tragedy today. In the case of the Armenian genocide, we’re talking about something that’s still not universally recognised, 109 years after the fact. Only last September, 150 000 Armenians lost their ancestral homes in Artsakh and have been displaced, so it continues to unfold.

And in that sense it’s interesting what Komitas represents: a pushback against the attempt to erase and silence these people culturally. When genocide is perpetrated, of course the ultimate aim is the extermination of the entire group (that’s why we have the term, coined by the Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin): they go after the women and children to prevent future generations, and they go after the culture. And Komitas saved so much of this culture by writing down these 3000 songs that survive (there were probably more, but some of his papers were lost).

Komitas physically survived the genocide, but he was mentally, emotionally and psychologically destroyed; he spent the rest of his life in hospital, silenced because he could no longer write. These Armenian Dances for piano that I’ve recorded are the final creative act that he was able to undertake, so in a sense he exemplifies the tragedy of surviving but losing your voice and identity.

Who ensured the survival of his music?

I think it’s partly because before the Armenian genocide and his breakdown Komitas was already recognised as an important national figure; when he was first imprisoned in 1915 he was released after international pressure because he was so well-known. The survival of his music was maybe on the radar because much of it was already published before the catastrophe; the people who took care of him during his illness also ensured the transmission of his papers from Constantinople to Paris and what was then Soviet Armenia.

Even its publishing history is so intertwined with politics. As a child I was aware of this music peripherally, because it entered the lore of the music of the Soviet Republic; there were attempts at ‘cleaning up’ a lot of the scores, and in fact the music that we used for this recording was printed from 1940s Soviet editions.

How did the programme itself take shape?

I ended up in France at the start of the pandemic, and I was immediately drawn to the Debussy Études - partly just because I’d always wanted to learn them, but also because I felt a certain resonance with our situation. Of course living through the First World War was immeasurably more awful and tragic than anything we were going through, but when I started thinking about Debussy isolated in a Normandy village during another kind of lockdown situation the idea began to take shape. I started exploring other music written in that dark time and situation, and that’s when I thought of Komitas and the connection between them.

I decided to pair the Études with Komitas’s Armenian Dances, and alongside the Études I felt it was imperative to record En blanc et noir for two pianos because he wrote the two works adjacently; when one plays both pieces it’s absolutely clear that the musical DNA is the same. I’ve played the piece a lot with Thomas Adès, and I thought it was quite important to preserve Tom’s vision of this piece. As a composer-pianist he brings a unique perspective, so it’s a very special thing – not just two pianists getting together!

Then I started looking at what else Debussy composed during the First World War, and came to the opinion that we should include all these small pieces: Les soirs illuminés, the Élégie which is so forward-looking, and the Berceuse héroïque which is very directly related to the War. I asked Katia Skanavi to join me for the four-hand version of Épigraphes Antiques, which is the only piece Debussy wrote in the year the War started.

We know that Debussy heard Komitas’s setting of Antuni (an iconic Armenian song about homelessness), and there’s so much common ground between that piece and Debussy’s Christmas Carol for the Orphans of the War. They share one paragraph of words which are very alike: Debussy wrote the words to the carol himself, possibly after hearing the Komitas song, and Debussy's song was premiered in the same programme as Antuni was sung at a benefit concert for victims of the Armenian genocide in 1916. The Chansons de Bilitis were composed much earlier, but this was a cycle that Debussy often chose to play at benefit concerts during the War, so that’s why it’s included here.

Where did you record?

One positive side-effect of lockdown was that we could get access to the most amazing acoustical spaces: the solo works and Épigraphes Antiques were recorded in the large hall at the Konzerthaus in Vienna, which is never available or affordable in normal times. The administration of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York managed to stop construction for three days so we could record with Tom Adès; the songs with Ruzan Mantashyan were done at the Siemens-Villa in Berlin where many legendary vocal recordings were made, including the Schubert cycles with Fischer-Dieskau.

You mentioned ‘shared musical DNA’ earlier – is there much of that between the two composers?

No, and that’s one of the things which I imagine intrigued Debussy about Komitas - that it’s such different music. There’s one shared element which I’ll come to in a moment, but essentially it works by contrast: Debussy was already fascinated by music from other cultures, and I think that’s partly why he was so struck by Komitas (as were D’Indy and Saint-Saëns) when heard this other way of making music.

What Komitas does in a very non-intrusive and tasteful way are these mini-harmonisations which don’t necessarily come from Western harmony per se: it’s not Europeanising or colonising this music, but simply giving it a certain particular definition that he wanted. And another amazing thing is how he melds his own personality with the folk material: even scholars are unsure about which passages were composed by Komitas, which ones are based on folk music, and which ones are direct transcription. Even within a single piece it often appears to be an ever-changing balance between the three: Antuni is a wonderful example of that. In a very different way it reminds me of my favourite, Mr. Ferruccio Busoni: if you look at a piece like the Fantasia contrappuntistica you’d be hard-pushed to pinpoint where it’s Bach, where it’s Busoni, and where it’s a mixture between the two…

The one element which the composers do share is a certain spaciousness within the sound-worlds, which is why I wanted to record in the large hall of the Konzerthaus: not for the loud passages, but for the softer things. There’s a particular lonesomeness in the sound, especially when you hear the individual lines unfolding in that huge acoustical space: that’s almost always present in the music of Komitas and (albeit with a different accent) in late Debussy.

On a purely manual level the Armenian Dances are a lot more straightforward than the Debussy Études, which are among the most difficult pieces in the repertoire – Debussy described them as ‘a warning to pianists not to take up the musical profession unless they have remarkable hands’! But the challenge of Komitas is a holistic one: it’s about conjuring atmosphere, creating something within the sparseness of texture, imitating the various folk instruments that are implied by the music.

In your introduction to the project, you describe En blanc et noir as 'Debussy's most overt anti-war statement' - how does that manifest itself in the music?

It comes as close as Debussy ever did to agitprop music. There’s a wonderful quotation where he says that he wrote not ‘war music’ but ‘music in a time of war’. That’s an important distinction, and it raises a question which still resonates today: as civilians, as artists, what can we do in these troubled times? Debussy certainly struggles with this, as we see in his writings: he can’t go to war because he’s too old, but he feels compelled to do something. He doesn’t want to write something banal and blatantly partisan, like a marche patriotique, but he feels he can’t ignore what’s happening around him.

And in this piece he uses quotations to explore that. For example, he juxtaposes the Lutheran chorale Ein feste Burg with a French song, the Marseillaise; the treatment of the chorale is overburdened and pompous to present a very negative view of that culture, whilst the Marseillaise is given this idealised, patriotic presentation. Then at the beginning of the second movement he evokes lone military trumpets which are clearly meant to represent the French soldiers in the field, so there are direct references to how Debussy viewed the two cultures locked in this mortal struggle.

The title En blanc et noir among other things refers to the piano-keys, but the piece itself is anything but monochrome: it’s bursting with all the colours of the rainbow! One of the messages from the whole album is that music in time of war is not all dark – there’s certainly tragedy, gloom and heartbreak, but also an incredible amount of exuberance, kaleidoscopic colour and life-affirmation which is the antidote to the greyness and blackness of war and genocide. I see that as a comment on the resilience of the human spirit, and the creative spark that can’t be extinguished even in the darkest moments.

The physical album is an absolute treasure-trove of scholarship: how did you go about curating it?

The idea was to contextualise this music – it’s part of a wider discussion about whether we can appreciate art in abstraction. I guess the answer to that question is ‘Not really’, or at least not as fully as we can when we put it in context. It’s also a commentary on why a recording needs to be available as a physical product in 2024, and I think this album captures something which we lose in streaming: the text, photographs and illustrations. The finished product is more stunning than we hoped – it’s really a coffee-table hardcover book, and at 180 pages it’s an object in its own right rather than just an enlarged booklet.

I decided I wanted a certain symmetry in the book: two musicological essays (one on each composer), and two historical ones. For Debussy I convinced the composer Heinz Holliger, who expresses most insightful and original thoughts on these pieces, and the Komitas essay by Artur Avanesov is the most inspiring thing I’ve read about him in the English language - it does a wonderful job of exploring what Komitas means in Armenia and beyond. Renowned French historian, Annette Becker, contributed an essay on artists during wartime and Armenian historian Khatchig Mouradian wrote about cultural resistance during the Armenian genocide. Everybody who contributed to this project is an amazing person in their own right, including the editors and translators: Richard Evidon, for instance, edited the Grove dictionary for decades and spent twenty years at Deutsche Grammophon and Eva Zöllner translated the books of Charles Rosen into German, so the level of skills is off the scale!

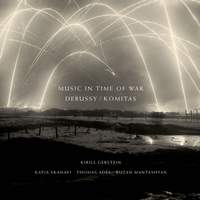

The cover was created by Peter Mendelsund, who was described by The New York Times as ‘one of the top designers at work today’; he used a documentary image of the Battle of the Somme, and I got permission to reprint the facsimile of Les soirs illuminés for the first time. So the ingredients and contributors are just amazing. Thus, I hope that this album can be an immersive experience that gives aural pleasure and prompts thoughts on these important and ever-pertinent subjects.

Kirill Gerstein (piano), Ruzan Mantashyan (soprano), Katia Skanavi (piano), Thomas Adès (piano)

Available Formats: 2 CDs + Book, MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV