Interview,

Rory Macdonald on Our Gilded Veins

I spoke to Rory last month about the orchestra's reputation for commissioning and championing new repertoire, the overarching themes on the album, some of the fascinating compositional techniques involved, and the relationships which have sprung up between the featured composers and artists.

How did this fascinating programme originate?

We had the opportunity to record some contemporary repertoire with Linn, building on our recordings of the symphonies of Thomas Wilson, who was probably the pre-eminent Scottish composer before the emergence of Sir James MacMillan. The Royal Scottish National Orchestra has been doing a lot for contemporary music in Scotland in recent years; a lot of these pieces are RSNO commissions, and it’s lovely to have a record of that.

I think there’s still a place for a curated mixed disc, even in an age where people can buy or stream individual tracks; portrait albums of individual composers are great too, but there’s something nice about putting together quite a diverse mix of things with links and contrasts, rather like the recent Dalia Stasevska mix-tape album. Together we came up with this selection and realised that there is a connecting thread in that a lot of the pieces deal with themes of loss, memory and healing.

How do those themes play out in the opening piece on the album?

We begin with Jay Capperauld’s flute concerto Our Gilded Veins, which was written just before the pandemic and was finally premiered in 2022. That piece deals in a sense with issues of mental health, and it’s inspired by the Japanese art of kintsugi: when a piece of pottery is broken you can mend it with a beautiful golden lacquer. The idea is to highlight and make a feature of the break, and this acts as a metaphor for embracing imperfections rather than hiding them. So the piece in a way is about healing from some sort of trauma; the flute soloist personifies somebody who has had something traumatic happen to them, and the rest of the piece is about how they come to terms with that. The piece starts the album with a bang: it's scored for very large forces and is absolutely teeming with orchestral detail and flurries of ideas.

It was written for the RSNO's Principal Flute Katherine Bryan, who has probably done more than anyone else today to expand the flute repertoire: we were just saying before the recording-sessions that you could probably count the number of flute concertos which are regularly performed on the fingers of one hand! It’s also an example of the good work that the orchestra’s been doing with young composers; Katherine heard and loved one of Jay’s pieces when he was part of the RSNO Young Composers' Hub back in 2016, and that’s how this concerto came about. Jay is now a mentor on their latest scheme for young composers, Notes from Scotland, so it’s wonderful to see how things come full-circle. Another nice connection is that Martin Suckling, whose music features later on this album, also wrote a beautiful concerto for Katherine a few years ago.

Was it a conscious decision to follow that with a work for strings-only?

Indeed: next we have two beautiful, much smaller-scale, intimate pieces, the first of which is Anna Clyne’s amazing work for fifteen solo strings, Within Her Arms. The world premiere was given back in 2009 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic with Esa-Pekka Salonen, and I conducted and fell in love with it a couple of years after that.

It’s an incredibly fragile elegy in memory of Anna’s mother, and it begins with a very simple four-note motif from which she builds an extraordinary, layered lament. Every string part is a solo part, so in a way it’s in the tradition of something like Strauss’s Metamorphosen, but there’s also a lot of inspiration from the English Renaissance (particularly Tallis and Dowland). It has really embedded itself in the string repertoire already and has had hundreds of performances all around the world, so I was thrilled that we were able to make the first studio recording. It's a very moving work.

Although the album focuses mainly on Scottish composers, Anna has very strong links with Scotland. She studied music at Edinburgh University and has just finished quite a long stint as composer-in-association with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, so a lot of her work has been premiered in Scotland.

You mentioned Sir James MacMillan earlier...what's the story between the two works of his on the album?

The first of Sir James’s pieces is For Zoe from 2022: it was written in memory of Zoe Kitson, who was the Principal Cor Anglais of the orchestra from 2006 until 2014. I knew Zoe too, because before she joined the RSNO she used to be a guest principal at the Budapest Festival Orchestra (where I was working with Iván Fischer); we were all devastated by her very early death, and the piece was commissioned in her memory by the RSNO.

It’s an incredibly beautiful piece, scored for solo cor anglais, harp and strings; for the most part it’s a very simple, lamenting cor anglais line with a more animated section for solo strings in the middle. The orchestra has just taken it on their recent European tour. We all love the piece and it will certainly have a long life beyond this recording; it's a great addition to the cor anglais repertoire, inhabiting the same sort of sound-world as Sibelius’s The Swan of Tuonela.

Coincidentally MacMillan’s The Death of Oscar (which comes next) also features an extended cor anglais solo at the end. This piece was commissioned by the RSNO back in 2012 when Stéphane Denève was Music Director (a co-commission with the Seattle Symphony and the SWR). It’s completely different in style from the previous piece, although it fits within the theme of remembrance and loss because it’s about the ancient Celtic warrior and bard Ossian and the death of his son Oscar.

The music starts in a brooding, mysterious, dark place and gradually builds to a slightly militaristic episode in the middle where we hear some sort of battle happening; then comes that beautiful elegiac passage for cor anglais, which almost sounds like a pibroch lament. It’s a really impressive tone-poem, telling a story from beginning to end – again it reminds me of Sibelius in that it conjures up an ancient world, and there’s a wonderful mixture of different tempos and styles within it. It’s scored for a very large orchestra and is extremely cinematic: it’s a lot of fun to play, and I think it’s an important piece within MacMillan's oeuvre.

I gather that the following piece, Martin Suckling's Meditation (after Donne), involved a sort of sonic crowdsourcing..?

From that description of an ancient saga, we go to something more contemporary with Martin Suckling’s piece, Meditation (after Donne); it was written in 2018 as part of the Armistice Centenary commemorations for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, when Martin was Composer In Association. I remember thinking what a brilliantly simple idea it was at the premiere: it was inspired by the moment of Armistice, when all the church-bells across the country rang out having been muffled or silent throughout the course of the War. What an incredibly moving experience that must have been.

The orchestra did a social media call-out asking people across Scotland to send in recordings of their local church-bells, and they were inundated with recordings from little villages as well as larger towns. Martin brought these bell recordings together, and when the piece was premiered they set up surround-sound speakers in the hall so that the sound of the bells really enveloped the audience: the recordings are then cued in time with the music.

The orchestral forces are quite small - strings, woodwinds, horns and trumpets - but with this incredible overlay of bells from all around Scotland. What’s also really clever is the way in which Martin has seamlessly melded the orchestra and bells together – he uses microtones quite a lot in his music, which creates a very special magical sound-world, and in this piece he’s actually found harmonies from the overtones of the bells, so that the bell sounds echo out with all their overtones and the orchestra is able to join and sustain those exact pitches.

What I like about all the pieces on the album is that they touch us emotionally: this isn’t always perceived to be the case with contemporary music, but all of the music here goes to the heart of the listener and I think Meditation is a good example of that. Martin describes it as ‘a simple song for orchestra’, and I’d agree with that: it’s based on very simple violin melodies (again with a real Scottish folk inflection to them), and he creates a special effect with the woodwinds where they press the keys of their instruments in time so that it sounds like a very distant marching army. (That was quite challenging to record, because it’s a very subtle sound!)

The piece is constructed around a very long chord progression which grows and grows, then suddenly this unexpected major tonal harmony comes out of the microtonal build-up; I think it’s very cathartic, and the music ends very quietly. In several of the recordings that were sent in you can hear background noise, so it ends with birdsong in the background - a beautiful, peaceful conclusion.

The conclusion to the album itself is one of the best-known pieces of twentieth-century music associated with Scotland, Sir Peter Maxwell Davies's Farewell to Stromness - how does that fit into the grand scheme of things?

For the final track we wanted to record something simple: there’s a lot of dense writing to take in on this album, so it was nice to end with something very pure. The piece itself is quite famous, but what’s perhaps not so well-known is that it was written as a protest against potential uranium-mining in the Orkneys where Maxwell Davies lived, and it's perhaps all the more powerful for its understated dignity. It’s become very popular at both funerals and weddings: indeed King Charles and Queen Camilla had this string arrangement played at their wedding blessing in 2005. The melody has taken on a life of its own, and even though Maxwell Davies composed it himself you might assume that it was an authentic Scottish folk-melody.

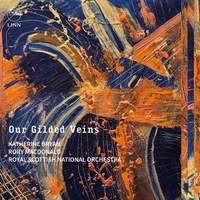

The cover-image for this recording is stunning: was that commissioned especially for this project?

It's beautiful! It's an original work by Anna Clyne, who uses painting quite a lot in her work. In fact she created an enormous wall painting in preparation for her big orchestral work Night Ferry (written for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra), and that acted as her map of the piece while she composed. We’re very fortunate that Anna made this picture specially for the album: it’s actually called Our Gilded Veins, and there are little shoots of gold in it referring back to the kintsugi techniques referenced by the opening track of the album. Jay Capperauld was Anna's successor as Composer in Association at the Scottish Chamber Orchestra - I think it's a lovely example of composers collaborating across different media and being inspired by each other's work.

Katherine Bryan (flute), Henry Clay (cor anglais), Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Rory MacDonald

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC