Interview,

Aziz Shokhakimov on Prokofiev (and Strasbourg)

In between sessions for their recording of Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé last month, Aziz spoke to me about the challenges and rewards involved in building a relationship with a new orchestra, navigating cultural differences in the rehearsal-room, making his opera debut conducting Carmen at the tender age of fourteen, and what he's looking forward to the most in the orchestra's upcoming season...

Homepage photo of Aziz Shokhakimov (c) Pascal Bastien.

You've just committed to two more seasons in Strasbourg, so presumably it feels like home now...how long did it take you to settle in after you took up the position in 2021?

At the beginning it wasn’t so easy, in all honesty, because my family and I had lived in Düsseldorf for six years; I’d been working there as Kapellmeister at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein and the moving process is always difficult, especially when you have young children. Adapting to the French culture was not without its challenges for us all, but that was made easier because Strasbourg is right on the border. It’s a city which is a mixture of the two cultures, German and French, and that makes this region unique.

The relationship with the orchestra took a little while to build, too: when I arrived here I had to really analyse how to work with the people, figure out what I was and wasn’t allowed to do, find the best way to express things, and get to know the players as individuals. But from the beginning of my second season I started to really enjoy being here: I’ve fallen in love with the city, and I have a very good relationship now with the orchestra. Of course we have our ups and downs, but in general I feel I can now enjoy the fruits of our collaboration.

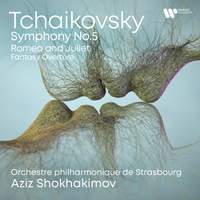

This Prokofiev recording was my first project with the orchestra: it’s our second release together, but we actually recorded it first. Perhaps it was a bold move to start with the Classical Symphony, because although it sounds easy there’s so much detail in there that you could work on every movement for days! But I’m very happy with the final result.

In terms of adjusting to the culture, did the differences lie mainly in repertoire choices or was it a question of the logistics and people-skills involved?

The main difference lies in the method of achieving the results you want with the orchestra. For instance in German-speaking countries, the players expect the conductor to tell them exactly what he wants, and they carefully write everything down in their parts; of course that happens in France as well, but it’s particularly crucial with German orchestras. I’ve worked a lot in Germany and still do, and the musicians like to know the precise musical details before getting to grips with the emotional side of the music – I love that way of working, but I’ve come to realise that there are other valid approaches. The French generally expect more emotional support and inspiration from their conductor: detail is also important, but it’s a secondary concern rather than the primary one.

When I got here I was very surprised that my new orchestra was very strong on Austro-German (and Russian) repertoire, but not so used to playing French music! We had to work hard on the colours and details, but now I think we’ve improved this part of the orchestra’s repertoire. Our main aim is for balance in our programming, because we want to show the many different cultures which exist in Strasbourg: there’s only one professional symphony orchestra in the city, and I think it would be a limitation to focus our attention on one composer or style for a whole season.

Have you conducted much in the UK, and if so how did you manage with our often quite minimal rehearsal-time?

Just twice: I conducted the Royal Scottish National Orchestra many years ago, and I did a concert with the London Philharmonic at Brighton Dome back in 2014. That feels like a very long time ago, and on reflection I was too young! The programme was music that they’d played many times - Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 and the Beethoven Violin Concerto - so I only had one rehearsal before the concert. And I demanded a lot in that one rehearsal. I had strong ideas about my interpretation of the Brahms, so I wasn’t willing to follow the players: I wanted them to do what I wanted! It wasn’t easy at the time, but it was a brilliant experience in terms of learning how to work with a great orchestra that’s used to playing core repertoire with great conductors.

Speaking of doing things at a young age, I gather you made your professional conducting debut in your early teens! How did that come about, and who nurtured you at the beginning?

When I was about five my mother asked me if I wanted to play an instrument and I chose the violin, but my childhood dream was actually to be a composer. Then when I was 10 or 11 I started to sing, mainly Italian and Neapolitan songs: ‘Santa Lucia’, ‘O sole mio’, that kind of thing. The conductor Vladimir Minin happened to hear a recording, and invited me to perform as a singer with his chamber orchestra. I remember him saying ‘Aziz, when you sing you have a kind of energy which I like very much – you’re a very musical guy, and I’m going to give you some co-ordination exercises to help your high notes’.

He was very surprised that I could manage them quite easily, and that was a sign of things to come: it’s very important for a conductor to have independence of the hands. Vladimir noticed and nurtured that, giving me piano pieces to orchestrate and explaining about transpositions of instruments. Then he allowed me access to the youth orchestra, which was great experience because different instruments were often missing in rehearsals: my job was to play the horn part or clarinet part (or whatever we didn’t have!) on the piano, and that was a natural way to understand transposition.

I was still persevering with my violin lessons alongside all of this, but when I was 14 the programme got quite difficult at the school where I studied. My teacher was the concertmaster of the orchestra, and after listening to how I played the set repertoire he said ‘Aziz, maybe you won’t be the greatest violinist, but I’m sure you’ll make a very good conductor one day! Maybe switch to the viola in the meantime…’. The student viola repertoire isn’t as technically demanding, and I changed over pretty much straight away; when I started at the conservatoire I spent two years playing principal viola with professional orchestras, and it was very useful to spend that time on the other side of things.

When did Prokofiev's music enter your repertoire, and what specific technical challenges do the works on this album present?

I was 15 or 16, I think: it was Symphony No. 7 and the Piano Concerto No. 1. I read Prokofiev’s autobiography when I was preparing for the performances, and I felt a very strong connection to him on a personal level at that age: I could really identify with a lot of the ideas and emotions he expressed, both in the book and in his music.

The tempi which Prokofiev writes in this specific symphony are quite doable, and I tried to stick to them in my interpretation. But there are certain passages where the indication by the composer maybe isn’t feasible for the particular situation: for instance, if you’re playing in a church you have to do things a little slower or it doesn’t work. Your interpretation has to adapt to the acoustic and even the level of the orchestra, and that can be a difficult thing to gauge. In some passages you might need to sacrifice momentum in order to play absolutely together, because the beauty of the music lies in the ensemble.

But equally there are times when the ensemble might have to take second place, because bringing energy is the most important thing. When I conducted Lohengrin (which is full of all sorts of technical challenges for the players) in Strasbourg there were a few moments where maybe it wasn’t 100% together, but that was a risk I was willing to take to generate the emotional excitement which the drama needs.

The new album also includes the suite from Romeo & Juliet - does your work in the theatre extend to ballet as well as opera?

I conducted a few ballets when I worked as Kapellmeister in Düsseldorf, and about twelve years ago I did a few performances of The Rite of Spring for a production in Bologna. Working on ballet is an incredible experience for a conductor, because it’s really another world from opera: the choreographer will often ask you to take a particular tempo, and if you alter it even a little bit then everything on stage can fall apart! But I found that sometimes the dancers actually like it if you push the tempi on a bit, because you’re generating some energy for them. I like to think of them dancing on the music rather than just with it: very often it’s much easier if the music is leading them rather than following.

Last spring you stepped in to replace an unwell John Nelson for a concert-performance of Carmen (an opera which also contains a lot of dance music!) in Strasbourg - was the piece already firmly embedded in your repertoire?

I know the score almost by heart – I could conduct that opera on a moment’s notice! Carmen is very special for me, because it was my first-ever opera: I conducted it for the first time when I was 14, at the opera house in Tashkent. (We did everything in Russian back then, which made things a bit easier for me, but now things have started to change). It was also the first thing I guest-conducted in Düsseldorf to get my job as Kapellmeister, so it’s become a bit of a calling-card.

Your current role in Strasbourg includes both operatic and symphonic work: would you ever be tempted to take a full-time opera-house job, or do you like to keep both plates spinning?

That’s a question I’ve been pondering a lot, and I think the answer is that they have equal priority for me. I’m convinced that it’s incredibly important to do both operatic and symphony concerts, because so much symphonic dramaturgy is based on opera. That’s why I always search for operatic elements in symphonic music, and vice versa: it brings more richness to both. My one frustration about conducting opera is simply the longer gestation-period – sometimes it can take five weeks to bring a production to the stage, and I’m the type of person who can get a bit bored by repeating passages so much during production-rehearsals!

The repertoire for the new season in Strasbourg was announced at the end of last month: what are you looking forward to the most?

It has to be Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, which I’ve never conducted before – I’ve dreamed of it for a long time, and it’s very hard to get the chance to do that piece as a guest conductor because it’s always the priority of the Music Director! Finally I have the opportunity: I’m going to do it here in Strasbourg, and also in the opera house of Torino with their orchestra…

Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, Aziz Shokhakimov

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV

Orchestre philharmonique de Strasbourg, Aziz Shokhakimov

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV