Interview,

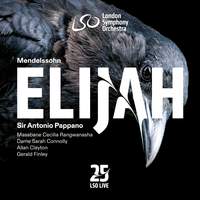

Antonio Pappano on Mendelssohn's Elijah

In anticipation of the release of their recording of this mighty work on LSO Live tomorrow, I spoke to Maestro Pappano about how his experience as an opera conductor helped him to bring out the narrative thrust of the piece, the central role that the chorus plays in maintaining the dramatic momentum over such an extended musical span, how his interpretation changed when conducting it in English rather than in German, and the ways in which Mendelssohn’s debt to JS Bach manifests itself throughout the work.

With a lengthy piece such as this with so many relatively short movements, it can sometimes be difficult to maintain the momentum, but I was very impressed with your pacing and how you kept the dramatic flow. How do you deal with that kind of structure?

Well, it's an opera, isn't it? It's a piece of declamation with a commentary, and the narrative is very strong. The descriptive nature of the orchestral component goes without saying, you can hear it immediately. It has an incredible energy and flow. Yes, that is interrupted by recitatives to declaim or to inform people of what's going on, as oratorios do - but it's interrupted by the greatest adagios that are so genuinely contemplative, not only for the soloists, but for the people who are listening to them.

But the choruses are so full of genuine character. Obviously the models are the St Matthew Passion and particularly the St John Passion, where the chorus is really aggressive and misguided as they are in this. And that's why I call it opera. I say opera: well, I would, I'm an opera conductor! Of course I would see the operatic elements. It certainly influenced the earlier operas of Richard Wagner, despite his hatred for somebody like Mendelssohn, an ultra-gifted, Jewish composer. There's no question that pieces like The Flying Dutchman, Das Liebesverbot, and Die Feen are totally imbued with a Mendelssohnian flair.

You talk about it being like an opera: do you therefore cast different types of voices than if it were a more traditional oratorio, and what do you look for in your principal singers?

Unique personalities! I believe this piece is best served by operatic voices, certainly the declamatory nature of the Elijah role. All the people that sang in these performances are operatic singers but who also have a tremendous experience in oratorio. They're all comfortable on the concert platform, and so I've got the best of both. I think that that's what you have to look for, that sensibility for the right combination of dignity and thrust. It's elusive but there are great singers who can do it and I think I have four of them.

To move to the orchestra, how interested are you in so-called historically-informed performance practices in terms of use of vibrato, playing style, and so forth? And did you opt for any period instruments such as using an ophicleide instead of a tuba, for example?

No, we didn’t use an ophicleide; it’s a very precarious instrument and very unreliable! There was nothing else like that in terms of original instruments; it just felt like it would have been a gimmick: to have used original drums, original trumpets, original horns and so on would have been something else.

What you will hear on this recording is very considered use of vibrato, tending towards “less is more”, and this is a way to get the serenity of the slow movements. If you hear the way the cellos play in the great baritone aria, 'It is Enough', it could almost have been a baroque ensemble. That was achieved particularly by principal cellist David Cohen: it was his courage to bring the group with him and, with a little bit of information about what the text was saying, how could we get this to be something special and expressive.

Mendelssohn’s relationship to Bach was very strong, especially with the revival of works such as the St Matthew Passion, and so I think you have to take that into consideration. How do you achieve the greatest sense of serenity and drama? How does the vibrato influence that? Where does the vibrato bring the music into a sentimental area, which is inappropriate for this music? How do you get the most thrust on dissonant chords? So I've thought about it a long time, and you could say the performance is historically-informed to a certain degree, but not whole-hog, because that's not me. I don't come from that world, but I'm aware of it - and where I can use it to better sell the music, then I use it.

What I'm more preoccupied with is the communicativity of the singers and the choir. We chose to perform the piece in English as it was premiered in Birmingham. I'd never conducted it in English: I've always conducted it in German, and together with the soloists, I took the time to really rethink some of the Victorian English. Some of it just sounds ridiculous today, and so we've tweaked it here and there. We've tried to avoid some of the clumsiness of the language, but more importantly than that we've tried to better achieve the accents. The piece was obviously written with accents in German, and we thought we could improve some of the syntax and where the emphasis falls by tweaking the English text. I took it upon myself to make those changes, I think for the betterment of the comprehension.

And beyond this tweaking of the text, did you find yourself changing your interpretation much because of the different language?

There's no question. The ability for that kind of sound of the English chorus to achieve greater rhythmic nimbleness certainly affected the way I conducted the piece. I mean, you conduct in the language you're performing in. German requires a certain approach, and when you're conducting in English, it's a different approach. It just is. I think you have to be faithful to what you're doing at the moment and not achieve some kind of rarified idea. These are taken from live performances, with very little patching or editing, and it’s a view on the piece with wonderful soloists that I think is legitimate.

Speaking of the chorus, obviously there's a chorus director but with very chorus-heavy works such as this, how involved do you like to get in shaping their contribution?

For Elijah we had two separate sessions, one on each half, where I talked through the score with chorus director Mariana Rosas; we talked specifically about every bar and certain text changes, but also the delivery of the text, the type of articulation I was looking for and the type of drama that I think the piece is begging for. If it doesn't come from the chorus, then you're lost, because the piece is so long and therefore you're constantly challenging the audience's attention. I think that's what show business is: you have to be very specific and you can't just invent it at the rehearsals: you have to have an idea of what you want to achieve, and then see if it works. Is it working to the level that you need it to work? And she prepared the chorus beautifully for that.

Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha, Sarah Connolly, Allan Clayton, Gerald Finley, London Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra

Available Formats: 2 SACDs, MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res+ FLAC/ALAC/WAV