There may come a day when Arthur Berger (b. 1912), with his twin talents as composer and critic, will be regarded as his generation's Robert Schumann, who likewise excelled at both. Their impact on the music and thought of their respective eras is similar. Both composed works of great beauty, while maintaining a keen ear for the musical achievements of others-Schumann instrumental in Brahms' success, Berger championing the work of Ives, Copland and many others.

Berger freely acknowledges beginning his mature career as a neo-classicist-taking the lead from Copland and mid-century Stravinsky-then shifting his methods to twelve-tone processes in the mid-fifties, influenced by Schoenberg and Webern. But ferreting out supposed mentors proves nothing more than intellectual name-dropping with a composer like Berger, whose own voice is so distinctive. Berger's synthesis of neo-classical and dodecaphonic approaches marks him as the foremost arbitrator between the two camps.

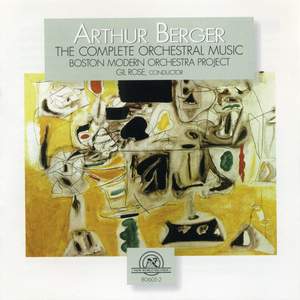

Berger's compositional output is small. These five short works, none longer than fifteen minutes-Ideas of Order (1952) Perspectives II (1985) Serenade Concertante (1944, rev. 1951), Prelude, Aria and Waltz (1982), and Polyphony (1956)-comprise his entire orchestral effort, and several of these pieces are themselves re-workings of previous settings. These compositions span five decades, yet Berger's language has an unmistakable underlying consistency. Two identifiable ingredients characterize these symphonic works: beautiful surface textures juxtaposed with adventurous rhythmic and harmonic experimentation. The former make each work compelling from the first listen; the latter reward careful study and reveal the depth of Berger's craft.