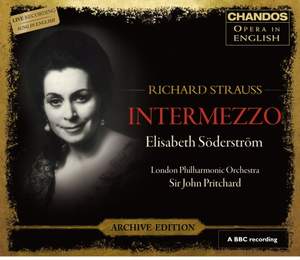

Elisabeth Söderström (1927-2009) stars in this live BBC broadcast of Richard Strauss’s comic and pioneering opera, Intermezzo, recorded at Glyndebourne in 1974. This unique performance is now available on CD for the first time as part of Chandos’ Opera in English historical series.

One of the great sopranos of the twentieth century, Söderström’s performances throughout the world were as famous as her many classic recordings. At Glyndebourne, from where this 1974 performance was recorded by the BBC, she appeared in some 13 festivals over a period of 25 years. Her performances of Richard Strauss were particularly admired. Invited to sing the central role of Christine in the first British performance of Intermezzo, this Swedish-born, multi-lingual artist insisted that it should be sung in English – contrary to the company’s policy at that time. She won the argument, as can be heard on the CD.

Glyndebourne’s George Christie sums up the characteristics of this great artist: ‘She was a consummate singer/actress – a mistress of bathos and an exquisite comedienne. She was beguilingly beautiful. Audiences fell in love with her as did her team-mates on stage – and off-stage. At Glyndebourne she reigned supreme. There was no lack of rivals, but she had an indefinable quality which made her the unquestioned, unchallenged queen.’

Intermezzo was first performed in 1924, and is based on an incident in the often turbulent, but enduring marriage of the composer, Richard Strauss, and his wife, Pauline. Strauss had yearned to write a work in lighter vein than his previous operas – and turned for his material to his marital life with Pauline. The storyline is about a wife who, feeling neglected and upset that her composer/husband is often away, goes off seeking enjoyment elsewhere. The fusion of music and dialogue is remarkable in the way that Strauss welds together lyrical outpourings, sprechgesang, the earthy dialect of servants and the polished language of their employers to draw fine characterisations, all underpinned by a brilliant score that illuminates the action. The opera draws an affectionate yet sharp portrait, employing many devices typically used in comic opera – misunderstandings, confused names, intercepted telegrams, and the like. Nevertheless, Pauline Strauss failed to see the joke (true to character), whilst audiences of the day thought Strauss’s thinly-veiled ‘portrait of a marriage’ in dubious taste. After Strauss’s death the work did gain in popularity, Glyndebourne’s production doing much to stimulate admiration for the opera in Britain.