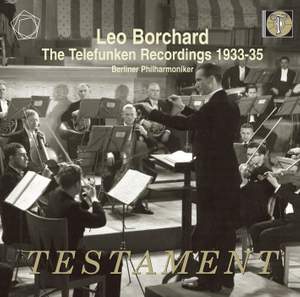

The present disc draws our attention to the unjustly forgotten musician Leo Borchard. Borchard was a musician, a cosmopolite and a resistance activist who became the first postwar conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Born to German parents in Moscow in 1899, Borchard came to Berlin in 1920, studied with Eduard Erdmann and Hermann Scherchen and gathered initial conducting experience with choirs. He was the répétiteur under Bruno Walter at the Deutsche Oper and under Otto Klemperer at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden and then the conductor of the Radio Orchestra in Königsberg for two years. On 3 January 1933 Borchard made his Berlin Philharmonic debut. Then on 10 December of the same year he conducted his second concert with a ‘varied programme’. During the 1935/36 season Borchard conducted the Philharmonic’s ‘Popular Concerts,’ leading the orchestra on fifteen evenings at the Philharmonic Hall in the Bernburger Straße. His concerts met with approval.

The 1936/37 season marked a negative turning point in Borchard’s career. Progress with the Berlin Philharmonic stalled. The ‘Popular Concerts’ were suspended – they no longer harmonised with official cultural policy. Borchard’s alleged political unreliability and critical stance toward the regime were obstacles to his rise; perhaps even his Russian birth played a role. In any case, he conducted only five more Philharmonic Concerts: an ‘English’ evening (5 November 1936) with works by Hamilton Harty, Arnold Bax, Ralph Vaughan Williams and William Walton; a ‘French’ evening (8 February 1937) with compositions by Hector Berlioz, Vincent d’Indy, Albert Roussel and Maurice Ravel; an ‘ItalianHungarian’ evening (11 March 1937) with music by Zoltán Kodály, Goffredo Petrassi, Béla Bartók and Alfredo Casella, and two Beethoven evenings.

In 1938 the journalist Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, with whom Borchard had become acquainted in 1931, introduced him to the Onkel Emil resistance group. The group hid members of the underground and political refugees, providing them with forged identity cards and documents, arranging for ration cards and engaging in industrial sabotage. The group aimed at Hitler’s war machine, forwarding information and situation reports to foreign countries, furthering the cause of political prisoners and supporting foreign labour convicts.

After World War II the Berlin Philharmonic soon established contact with Leo Borchard. He was the man of the hour. Since he was not burdened politically and had grown up with the Russian language and culture, he was able to negotiate in particular with the Soviet occupation forces, which soon also began working on cultural reconstruction. In June 1945 the Berlin authorities ratified Leo Borchard’s appointment to the post of the Berlin Philharmonic’s general artistic director. This made him – a fact often suppressed – the principal conductor of the Philharmonic, its fourth. He replaced Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had fled to Switzerland in January 1945. On 23 August, whilst returning by car from a dinner at the residence of a Colonel Creighton, he was shot dead by an American soldier on sentry duty. The English officer who was driving had misinterpreted the soldier’s command to stop at the sector boundary. Borchard was buried at the Steglitz Cemetery in the Bergstraße on 29 August 1945.