That a single note of Joao Laurenco Rebelo’s music has come down to us is thanks to two historical figures of great significance: Joao IV (1604-1656), king of Portugal, and Fortunato Santini (1778-1861), an Italian priest and lover of books.

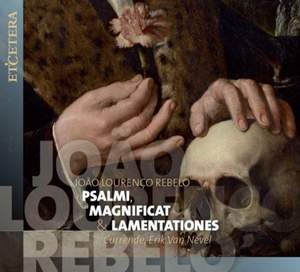

Joao (or John) IV became king of Portugal in 1640 after a rebellion against Spain, which had occupied its neighbour for more than sixty years. As Spain did not accept this monarchy, the new king was faced with a great many political (and military) worries. Despite this, he showed a greater interest in music than in the affairs of state. In his native city, Vila Viçosa, the seat of the noble dynasty of Braganca to which he belonged, he was trained in music by Roberto Tornar (ca. 1587-1629), a Portuguese musician with English roots who himself had been a student of the Flemish composer Gery de Ghersem (ca. 1573/75-1630), one of the singers in the ‘capilla flamenca’ in Madrid under Philip II and Philip III, and later Kapellmeister to the archduke and archduchess Albrecht and Isabella in Brussels. At the court in Vila Viçosa, Duke Joao made the acquaintance of the singer Joao Rebelo, six years his junior, who had been engaged as a choirboy there in 1624. In 1640, Rebelo followed the king to the royal court in Lisbon. Joao IV was a enthusiastic collector of music, as is testified by the catalogue of his library, the first section of which (published in 1649 in Lisbon) runs to more than five hundred pages, with a list comprising hundreds of music editions and manuscripts by Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, English and Flemish composers, a veritable goldmine. Tragically, this immense collection was completely destroyed by fire in 1755, during an earthquake in Lisbon, which also claimed thirty thousand lives. The king’s strong affection for Rebelo is clear from the dedication of his theoretical treatise, Defensa da la musica moderna (1650?) and, more important for us, from a clause in his will, drawn up two days before his death on 6 November 1656, in which Joao IV ordered a collection of sacred works by Rebelo to be issued in a printed edition. The following year, in Rome, there duly appeared an edition of liturgical compositions by Rebelo, entitled Psalmi tum vesperarum tum completarum, item Magnificat, Lamentationes, et Miserere (‘Psalms for Vespers and Compline, together with Magnificats, Lamentations and a Miserere’), for forces of between four and fifteen voices. Most of the works date from the period 1636-1653. This collection also includes two six-voice motets by the king himself. In his will the king had commanded that the composer make a gift of ten copies of the edition to the royal library, with the rest to be distributed for sale in Spain, Italy and elsewhere. Only one single copy of this edition has been preserved, thanks to Fortunato Santini. This Roman priest started assembling a unique collection of printed editions and manuscripts in 1796 (some autographs, including work by Handel, as well as copies). Thanks to his copies of countless compositions, a large body of repertoire, known only from this source, has come down to us. This invaluable collection was transported from Rome to the German city of Münster in the 19th century. It managed to survive two world wars essentially intact and is now preserved in the library of the Episcopal Seminary. The collection consists of approximately 4500 manuscripts and 1100 printed editions, including the single existing source for Rebelo’s work.