One of the most successful theatrical genres during the second half of the 18th century was, without doubt, the staged Tonadilla. By showing life in a cheerful, humourous and often shameless way, it attracted to the main theatres of Madrid, the Principe and the Cruz, a society wishing to be entertained with fresh and daring presentations of daily matters. An important component of the Tonadillas are seguidillas – songs based on popular dances – which were joined near the end of that century by the tirana, another musical form that had arisen from Spanish folklore. Both seguidillas and tiranas constitute links between the different social spaces that define the tonal identity of Spanish music at the end of the Enlightenment.

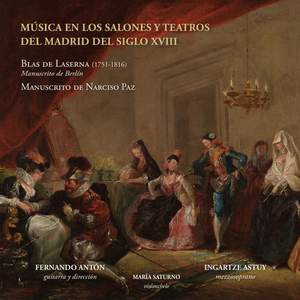

Beyond their popularity in the theatre, seguidillas and tiranas as a traditional form of entertainment were also performed in a more personal, private social space: the home. Thus were spread the jokes, the humour, the grace and the panache that emanated from these pieces – characteristics which reflected those associated with being “a good Spaniard”. A“good Spaniard” would appreciate the sharp and ingenious wit contained in these verses – as opposed to others who, turning their backs on the traditions of their elders, embraced foreign poetry and music. So it is hardly surprising that music teachers placed advertisements in the Madrid press, offering lessons in singing seguidillas and tiranas – while accompanying yourself with the guitar – so that youngsters of a certain class might augment their charms by emulating the artistry of the performers of the stage. Seguidillas and tiranas thus became infused with more domestic sounds and, as inheritors of tradition, propagated a vision of Spain that spread eloquently among the streets, squares, halls and theatres of the city in the form of songs.

In their most danceable origin, seguidillas and tiranas were accompanied on the guitar – the instrument that had long enjoyed widespread popularity in Spain. Being manageable and accessible, and with practical and easily learnt techniques for performing harmonies, the guitar had become the faithful and inseparable companion of the popular dance. In its ascent to the theatre, it was not limited to being yet another element in the instrumental repertoire of the tonadilla musicians, but rather shared the stage as a star in its own right: it was not just part of the decoration – as the musical instrument representing Spanish popular culture – but rather brought to the stage a sonority imbued with the everyday sounds of Spanish society.

In private homes, the popular seguidillas and tiranas could no longer rely on the wider range of instruments used in the theatres. The most apt and most easily adapted instrument to accompany this genre was none other than the familiar guitar. Musicians and composers understood this and adapted their songs in order to be played with just the guitar, or occasionally guitar and bass. These tunes entered bourgeois salons in the form of songbooks that were on sale in book stores, warehouses and other establishments. In the absence of a printing press specialised in sheet music, the scores that circulated in urban areas in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were written out by hand, either by dedicated copyists or by the composers themselves. Blas de Laserna (1751-1816), an acclaimed creator of tonadillas, established a store at the turn of the century where he copied music and wrote arrangements, selling both his own works and the best known compositions of other European writers. Among these publications there were also seguidillas, tiranas and other songs written for accompaniment with the guitar.