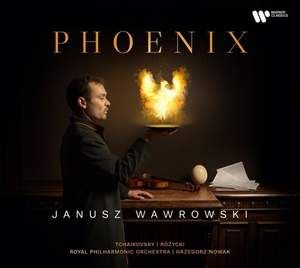

Janusz Wawrowski’s last Warner Classics album was Hidden Violin, a celebration of Polish composers and of his instrument – the Stradivarius ‘”Polonia” of 1685, the first Stradivarius to have come into Polish ownership since World War 2. His new album, Phoenix, could be subtitled ‘Hidden Concerto’. It pairs violin concertos by Tchaikovsky and the 20th century Polish composer Ludomir Różycki. While the Tchaikovsky has long been one of the world’s favourite violin concertos, the Różycki – an opulent post-Romantic work conceived during the traumatic Warsaw Uprising of 1944 – was never performed in the composer’s lifetime. Wawrowski premiered it in its current form as recently as 2018. For years, the elements of the score lay buried in a suitcase in the garden of Różycki’s deserted and ruined house in Warsaw.

During World War 2, the people of Poland were brutally oppressed by the occupying forces of Nazi Germany. Polish artists were monitored by the Gestapo, whose aim was to extinguish the country’s cultural identity. Różycki, born in 1883, had studied in Berlin in the early 1900s with Engelbert Humperdinck, the composer of Hänsel und Gretel. After World War 1, when Poland had gained independence from Russia, he was a member of a group of composers (including Szymanowski) who sought to reinvigorate their country’s music. He enjoyed particular success with his music for the ballet Pan Twardowski (1920), the story of a 16th century nobleman who makes a Faustian pact with the Devil.

Różycki worked on the violin concerto in the summer of 1944. (The Warsaw Uprising took place from early August to early October.) With the score well advanced in a version for piano and solo violin, he needed to complete the orchestration and, not being a violinist himself, to spend some time with the virtuoso Władysław Wochniak on the technical aspects of the solo part. When it became clear, however, that he and his family were in danger from the Nazi forces, Różycki decided to escape Warsaw – but not before he had hidden the manuscript in a suitcase and buried it in his garden. His house was eventually destroyed and after the war, Różycki, now teaching and composing in the city of Katowice, some 300km south-west of Polish capital, resigned himself to the loss of the concerto. He died in 1953. The buried suitcase was discovered by construction workers clearing the ruins of Różycki’s house in Warsaw and the scores that it contained found their way to the archives of Poland’s National Library.

Janusz Wawrowski takes up the story of the concerto. “It was some years ago that I first encountered fragments of the manuscript of Ludomir Różycki's violin concerto. This wonderful work spoke to me immediately, and the thought wasplanted in my head that, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, it should be reborn and enjoyed by audiences around the world.” With the help of a researcher and much scouring of archives, he managed to find the manuscript of the piano reduction of the concerto and, crucially, the first 87 bars of the orchestrated full score. Other musicians had already made completions of the concerto based solely on the piano reduction, but Wawrowski, working with the pianist and composer Ryszard Bryła, set about recreating the work, taking a crucial lead from the orchestrated fragment. He also edited the solo part to ensure that it lay well under a violinist’s fingers. The project took several years.

“The result, we hope,” says Wawrowski, “is as close to Różycki’s original thinking as possible … To me, the concerto is full of the energy and life of Warsaw before the war, and I think the composer was trying to conjure up and convey this positive energy as he wrote it in 1944 – a very dark time, as the artillery of the Nazis rained down on the city.

“Looking back at the turbulent history of our civilisation and at times of unrest, we see that culture and art have always played an essential role in humanity. Artists, in the face of sad realities, have consciously used their creative power to produce works bringing both hope and joy. This is the message of the two violin concertos recorded on this album. Both were written at very difficult moments in the lives of their creators – Piotr Tchaikovsky was seeking refuge in composition after the painful breakdown of his marriage.

“The two composers, although writing in different eras, created pieces that have much in common. Tchaikovsky [who wrote his concerto in 1878] is one of the first composers whose work resembles the style of film music as we know it today. Różycki's work reminds me of Gershwin or Korngold, with a slight glance towards Hollywood, yet retaining at the same time a distinct Slavic flavour. Różycki paints the solo violin part against the backdrop of a symphony orchestra in a manner similar to that of Tchaikovsky, despite the fact that he created his work 65 years after Tchaikovsky and with much broader orchestration at his disposal.”

Różycki work calls for no fewer than six percussionists and, like the Tchaikovsky, it is well suited to Wawrowski’s artistic personality: Gramophone has noted that “Wawrowski has a dark, luscious sweetness of sound, with warm vibrato,” while the Huffington Post has described him as “A virtuoso with the deep-souled tone of a poet.” He is joined for this recording by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and its Polish-born Permanent Associate Conductor, Grzegorz Nowak.

“It is incredible that Różycki’s concerto was written in the darkest times and carries such positive energy,” says Wawrowski.”In spite of the daily reality engulfing the composer, his spirit of hope for a better future was well and truly still alive.”